By Dr. Alison Kerns

Eczema and psoriasis are two of the most challenging chronic, everyday skin conditions encountered in dermatology. Both eczema and psoriasis tend to have a genetic component and they can be triggered by stress and environmental factors. Neither condition is contagious nor infections and they cannot be transmitted by external contact or exposure. They can easily be confused with each other so it is important to be able to recognize the difference between them so that we can understand the underlying cause and thus the best way to treat your unique presentation.

The term eczema is broad and is inclusive of a family of skin conditions including atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, dandruff, and others. Typically in dermatology, the term “eczema” is used to refer to atopic dermatitis (AD), a chronic inflammatory skin disease that causes dry, itchy, irritated skin. AD affects approximately 5 to 20 percent of children worldwide and has a prevalence in the U.S. of around 17 percent. The majority of AD presents before the age of five. In childhood eczema, food allergens are estimated to contribute to up to 30 percent of the cases.

The term eczema is broad and is inclusive of a family of skin conditions including atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, dandruff, and others. Typically in dermatology, the term “eczema” is used to refer to atopic dermatitis (AD), a chronic inflammatory skin disease that causes dry, itchy, irritated skin. AD affects approximately 5 to 20 percent of children worldwide and has a prevalence in the U.S. of around 17 percent. The majority of AD presents before the age of five. In childhood eczema, food allergens are estimated to contribute to up to 30 percent of the cases.

In eczema, the skin is dry, scaly, intensely itchy, red, and splotchy with raised lesions on the face, neck, upper trunk, wrists, hands, and in the “flexor” surfaces (inside the elbow and behind the knee) of the arms and legs. The lesions weep, crack, swell, and crust over.

It has been found that a mutation in the gene for the production of a protein called fillagrin is correlated with an increased risk for developing AD. Filaggrin is a protein that plays an important role in epidermal homeostasis or the proper development of the outermost layer of skin. This mutation can manifest as the skin’s function to retain water being diminished, causing dry skin and diminished protective barrier capability.

AD is considered an “atopic” condition because there is a predisposition towards a hypersensitivity allergic reaction. Eczema is considered a type 1 immediate hypersensitivity reaction and is associated with the formation of IgE antibodies (an immediate immune response) from exposure to allergens (environmental, irritants, food, animals, etc). It is associated with other atopic conditions, such as allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and asthma, and as a group they are referred to as the “Atopic Triad”.

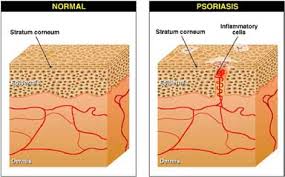

On the otherhand, psoriasis is a complex, chronic, relapsing/remitting, immune-mediated, multifactorial inflammatory disease characterized by red, scaly patches, papules, and plaques. It is caused by an overproduction of the cells in the epidermis (outermost layer of the skin), with an increase in their turnover rate. Environmental, genetic, and immunologic factors all play a role. The disease affects 2 to 4 percent of the general population. Although psoriasis may begin at any age, there seems to be two peaks in onset typically: one between the age 20 and 30 and another between the age 50 and 60. Gluten sensitivity appears to be common in psoriatic presentations, as well.

On the otherhand, psoriasis is a complex, chronic, relapsing/remitting, immune-mediated, multifactorial inflammatory disease characterized by red, scaly patches, papules, and plaques. It is caused by an overproduction of the cells in the epidermis (outermost layer of the skin), with an increase in their turnover rate. Environmental, genetic, and immunologic factors all play a role. The disease affects 2 to 4 percent of the general population. Although psoriasis may begin at any age, there seems to be two peaks in onset typically: one between the age 20 and 30 and another between the age 50 and 60. Gluten sensitivity appears to be common in psoriatic presentations, as well.

Where the rashes in AD can have irregular edges and texture, psoriatic lesions tend to be more uniform and distinct. Red or pink areas of thickened, raised and dry skin appear with a hallmark silvery scale on the scalp, the extensor surface (back of elbows and the front of knees) of the elbows and knees, lower back, and buttocks. In up to 30 percent of patients, the joints are affected and the skin lesions may vary in severity from minor localized patches to complete body coverage. Psoriatic lesions tend to be more common in areas of trauma, abrasions, or repeated rubbing and use, although any area may be affected.

Psoriasis comes in different types including plaque, guttate, pustular, inverse, psoriatic arthritis, oral, nail, scalp, chronic stationary, eruptive, and erythrodermic. Plaque psoriasis affects about 80 percent of psoriatic patients, making it the most common type.